“Cinderella” is the story that taught most of us how to view domestic chores for fantasy protagonists—namely, as a trap to escape on the road to their hero’s journey. Everyone needs clean clothes and something to eat. Children need to be watched, the sick not only dramatically healed but mundanely and conscientiously cared for, but for most fantasy novels, that’s a background process—support work for the questing party, nothing you can expect protagonists to do for themselves.

And then there’s domestic fantasy. The scope and the focus of domestic fantasy is often described as smaller than epic quest fantasy (note: these are not, of course, the only two sub-genres!), but more crucially, it’s also broader. It allows for a wider range of skills to be important, and a wider set of sources of agency through which characters can make an important difference in their worlds, by reexamining which changes and actions can be counted as important in the first place.

Lois McMaster Bujold once wrote a speech about science fiction as the fantasy of political agency, and many of her books are clear demonstrations of just that. But some of her most affecting and effective pieces have been the novellas that make the focus of that political agency excruciatingly clear—and strikingly domestic. In the multiple-award-winning novella The Mountains of Mourning and, nearly thirty years later, the related work The Flowers of Vashnoi, the issues of who deserves care and concern and how a culture decides to allocate those things take center stage on a very personal, very small scale. Elsewhere in the Vorkosigan Saga, these characters have been running planets, but the focus on the personal in these works intensifies rather than diminishes their agency.

In Patricia C. Wrede’s Dealing With Dragons, domesticity and political agency are inextricably linked. Princess Cimorene uses her housekeeping skills to win herself a place away from parental control: as a dragon’s housekeeper. Nor is her housekeeping entirely notional—a great deal of the book revolves around Cimorene cooking meals for a gathering of dragons, finding useful items as she tidies the dragon’s lair, and trying spells that turn out to have a lot in common with kitchen work. In a genre where “I don’t like girl stuff” is often used as a badge of honor to denote worthy protagonist material, Wrede gives us a narrative that values more than one skillset and allows for personal preferences among the “movers and shakers” of her world and her narrative.

Terry Pratchett’s Tiffany Aching is practically made of agency: She seizes life by the frying pan handle and goes after what needs to be done as though it was one of the cheeses she makes: gentle and subtle when possible, firm when necessary. Occasionally other people in the narrative attempt to push her into a position less domestic and practical—and less powerful—than that of witch. But she continues to lean into the value of care and common sense, and therein lies her strength.

Tavith, the heroine of Jo Walton’s Lifelode, is widely recognized, and occasionally underestimated, because her lifelode—her path, the tasks of her heart—is that of a housekeeper. She is the one who knows what plants are in season, what tasks will need doing while they still can be accomplished. And so Tavith is the one who makes life livable for an entire village when they are besieged. She nurses the injured and sends the magically gifted to speed the ripening of fruit so that everyone can eat; she takes the time to think about where people with different needs will sleep in a time of siege—and this is the important work of the book. This is not a sidetrack, this is not a charming interlude: It is the main matter of the story. Walton notes the ways in which people with other priorities think that their lifelodes are more important or more elevated than Tavith’s, but her narrative doesn’t support their assumptions.

The heroine of Pamela Dean’s The Dubious Hills, Arry, lives in a land where your life’s work arrives sometime around puberty, all at once, and where everyone has magic knowledge of one particular sphere of life that shapes their path. Arry’s sphere is pain, which conveys an accelerated responsibility and channels her into a very clear set of life goals. It is the work of caring for her younger siblings that gives her a significant part of the impetus to let her natural curiosity free, thereby catalyzing the entire magical and ontological change at the heart of the story. Her protective and caregiving nature propels her outward to investigate mysterious threats to the younger children she cares for–and to attempt to take the brunt of those threats wholly upon herself. If she was not a person who has to think about making porridge or potatoes or oatcakes for the kids, Arry would not be the person who successfully figured out puzzles, protected her village, and shifted the entire philosophical meaning of her life.

The parallel structures of a secondary world fantasy are often used for contrast, but Katherine Blake’s The Interior Life is structured so that this world and the fantasy world that its heroine contacts harmonize instead. As Blake’s heroine Sue gains confidence and agency through her access to a fantasy world, her interactions with our world get better, not worse. She makes her home more welcoming for others and, more importantly, more pleasant for herself; she takes steps to promote her own tastes and interests, but not at the expense of others. Sue is beautifully valued for work that is too often ignored or denigrated.

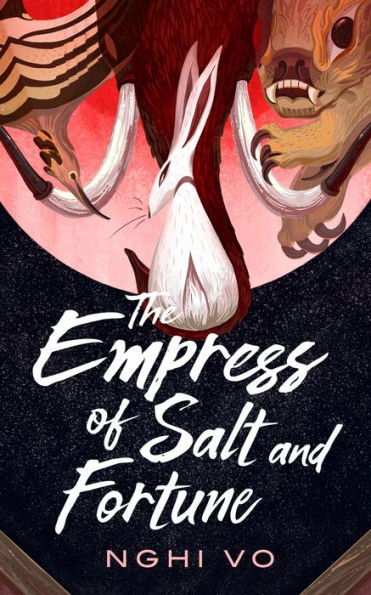

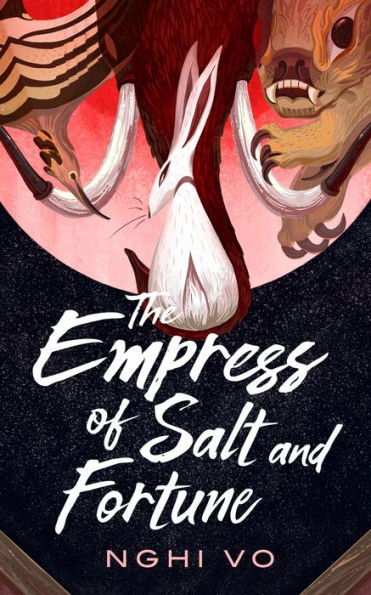

Buy the Book

The Empress of Salt and Fortune

Ntozake Shange’s Sassafras, Cypress & Indigo has a completely different story shape than The Interior Life, but its strength also lies in showing the value and indeed the magic in people whose circumstances are often viewed as constrained by domesticity. The three titular sisters each have different forms of magic and wildly different home lives once they leave their family home–but they are each shaped and enlivened both by their home circumstances and by their magic arts.

Which elements of agency are important to whom is a question Mary Rickert’s The Memory Garden never brings up overtly, but it doesn’t have to. The entire life’s work of the main characters, the story reveals, is to bring agency to women who would otherwise have it taken from them, in ways that haven’t always been possible in the protagonists’ own lives. Their magics are centered on garden and kitchen—small, specific, homely, but with reverberating impacts that spirals out from those loci.

Adding to the breadth of the subgenre’s treatment of agency, Caroline Stevermer doubles down on domesticity in Magic Below Stairs. It’s a sequel to the Cecelia and Kate series, co-written with Patricia C. Wrede, in which genteel women’s lives are considered with a sorcerous glaze—with domestic aspects similar to those later explored by Mary Robinette Kowal in her Glamorist series. But in this middle-grade follow-up, Stevermer shifts her focus from adult women of a higher class to their young orphan servant. Magic assists Frederick in his housework, but housework also gives Frederick a framework for understanding—and getting better at—magic. While there’s still a lot of focus on the upper classes’ needs and concerns, Frederick manages to make cleaning up others’ messes into a source of enchantment.

These books range across settings, protagonist ages, even category classification: Some of them center on weird gods and variable time flow, others on blacking boots or attending PTA meetings. But they all share a wider view of the world and of heroism, and of whose actions can matter. And I love that their answer is not that the farm boy matters only if he ceases to work on the farm and takes up a quest, or the ash girl if she rises into a ball gown and crown, but simply that the farm boy matters, the ash girl matters, the housekeeper, the caregiver—they all matter.

I believe that, and it’s its own kind of magic.

Originally published in May 2019.

Marissa Lingen is the author of over a hundred short science fiction and fantasy stories, including several here on Tor.com. She lives in Minnesota with two large men and one small dog.